Make the reader do some work

Recent ads from Heinz and Kellogg’s show how copywriting can turn the reader into an active player.

These brilliant new ads from Heinz commit a cardinal sin: they completely omit both the brand name and logo. The only clues to the advertiser’s identity are the typographic style and the reworked brand tagline.

The copy invites you to make your own connection between a Heinz product and a food that it naturally pairs with, inferring the identity of the brand along the way. For the baked beans version, for example, ‘It has to be Heinz’ becomes ‘It has to be toast’. (A subtle, possibly fortuitous parallel is that each replacement for Heinz also has five letters.)

Readers as accomplices

These ads get you involved almost against your will. They force you to play your part in the co-creation of meaning, and to do so in the service of the brand. As Arthur Koestler put it, “The artist rules his subjects by turning them into accomplices.”

However, you don’t resent this compulsion, because it’s a compliment too. The ads give you credit as a sharp cookie who can join the dots. They don’t have to spell everything out, because you can be trusted to do that for yourself. Besides, you’re far too sophisticated for anything as dreary as a tagline.

Now, instead of being a passive recipient who is merely told things – or sold things – you are a willing and active participant. Having collaborated as equals, you and the brand are on the same level and share a common understanding. You feel respected, acknowledged, seen.

This, in turn, infuses the experience with positive emotion, leaving you with a fond memory of your brief encounter with the brand. And with these ads specifically, that feeling is even more sensual and immediate if you like the food in question. (Readers outside the UK will just have to imagine that eating baked beans on toast is somehow acceptable.)

Original avian gangster

So far, so good. But what happens if the reader is intrigued by the puzzle, but still can’t actually solve it? That was a common concern over Kellogg’s recent ads that highlighted the ‘og’ within the brand name to position the Kellogg’s cockerel as ‘The OG’.

OG stands for ‘Original Gangster’, which refers to anyone who is long-serving or highly respected, often with a traditional outlook or approach. (They don’t have to be a literal gangster.) In the context of Kellogg’s, ‘OG’ exploits the age and heritage of the brand, and possibly its stuffy image, and gives them a playful twist.

Does everyone know what ‘OG’ means? Probably not. Not everybody knows every word in the world, and everyone has some words they don’t know. Yes, even me.

However, that doesn’t necessarily mean the ad will fail outright. The reader can still find out what OG means – by asking someone else waiting for the bus, the internet, a younger relative. Failing that, they can make an inference or a guess that might serve the purpose just as well.

And even if they never find out at all, the sense of intrigue is still there, as is the click of brand recognition. As with the Heinz ads, the feeling of encountering the ad is almost as important as its meaning (insofar as we can separate the two).

Intrigue vs irritation

The only risk is that intrigue curdles into indifference, or even irritation – the mental equivalent of hurling a Rubik’s cube against the wall. Here, Heinz is taking a bigger risk than Kellogg’s, since the reader could walk away without ever working out who the ad is for. But many marketing professionals were still furious at Kellogg’s for copywriting that they felt was elitist, inward-looking and self-satisfied.

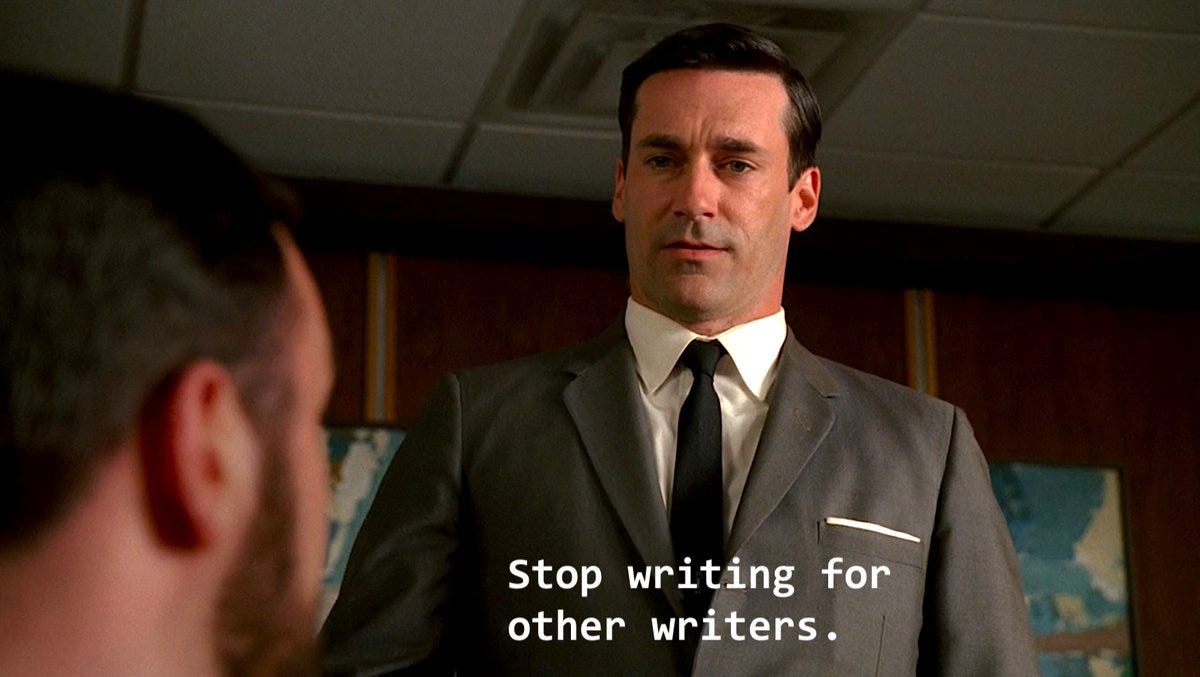

It’s a fair point. ‘Stop writing for other writers,’ as Don Draper tetchily admonishes a junior copywriter. Stop overwriting everything like a student essay. Stop making obscure, smug, smartarse allusions that no normal person will ever get. Stop winking at the D&AD judges and covertly furnishing your own portfolio. Instead, talk to the reader sincerely, in the words they would use themselves, and dramatise the benefits of the product as best you can.

However, I think both these ads are honest attempts to do just that. It’s OK to take the reader a little way outside their comfort zone if the message is more memorable as a result. And it’s OK to risk that message not landing with absolutely everybody if it reaches some people with greater force.

Every writer has to make a judgement on what to say and what to leave out. Say too little and people might be baffled; say too much and they might be bored. You take a risk either way. And in a world where most brands are so intent on tightly clasping the reader’s attention in both hands, it’s refreshing to see a few who are willing to loosen up and let the chips fall where they may. If you love somebody, set them free.